My recent guest post on persistence in the writing game at Chuck Wendig’s place was actually the result of the confluence of a few things. The night before I headed out to ConFusion last weekend, a regional convention in Detroit, I read Seth Godin’s The Dip: A Little Book That Teaches You When to Quit (and when to stick).

Anyone who’s followed my blog – in particular longtime readers who’ve been around since those first days back in 2004 – knows I’ve been writing a long time, and suffered a lot of ups and downs. It turned out that after all that time, getting my first three books published wasn’t the end of this road, though. Just like getting married or winning the sports trophy isn’t the end of a person’s story in real life, getting a book published isn’t the end either.

In truth, it’s just the beginning.

I happened to have a new series on submission, and was getting some very frustrating feedback. I started to question why I was in this game. If it wasn’t the money, or the copies, or the “fame” (oh god if any of you want fame, more power to you, but I’ll take money over fame ANYDAY)– what the hell was I in this for?

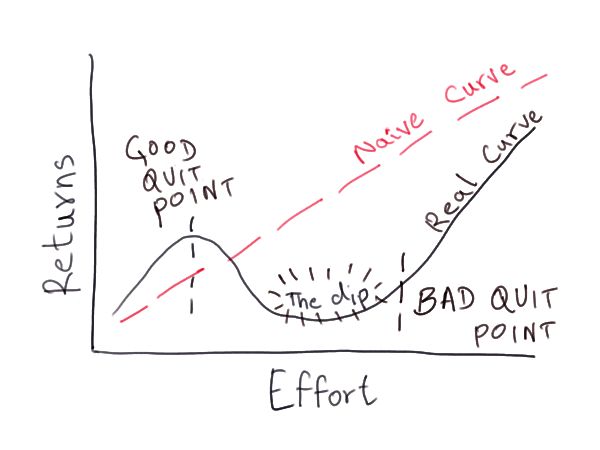

The “dip” in Godin’s “the dip” is the long slog you enter into with pretty much every new skill you’re looking to acquire. It’s after that first blush of fun and rush of getting good pretty quickly wears off (the way I felt after I went to Clarion, when I felt like I advanced 2 years in my craft in just six weeks), when all the sudden shit gets really hard, and you’re not seeing the results commeasurable with the effort anymore. It’s getting to that point when you’re finally getting personal rejection slips, but haven’t gotten a sale. It’s that time when you’ve already got a book published, but are pushing ahead to try and prove yourself with the next one. It’s the long slog when “getting better” takes far more effort than before, with less noticeable results.

And, unsurprisingly: the “dip” is when most people quit.

Godin argues that this is completely natural, this quitting. It’s part of the process. If we didn’t have the long slog, everybody would be a surgeon, or a lawyer, or a writer or a movie maker. Why not? Afterall, if you’re always seeing results that are exactly in line with your efforts, it doesn’t feel like a con – it feels like a natural progression. But we’re not all cut out to be lawyers and moviemakers.

The natural progression is the naïve way we *think* things are supposed to work. We think our results and our efforts should match. But no.

Here’s what Seth’s graph looks like:

Tons of people quit a new task just as it’s paying off there on the first rise. That’s totally fine if you’re pursuing something as a hobby. I am only going to get so good at gardening, or modding ponies, or making terrariums. I’ve reached the level I want to reach. I’m cool with not getting better. People who want to be the best at something, though, who want to be better than everyone else – who want to be master gardeners or master pony modders – need to keep going, keep pushing, keep improving, and inevitably, they hit the dip. The long slog.

The worst time to quit the dip, as shown in the graph, is right at the end, just when it’s starting to pay off. I’d say this is like quitting sending out stories just as you’re starting to get your first personalized rejections. Horrible time to quit. You’re actually just starting to come out of it.

The tricky part is that for many writers, there isn’t one dip. There are multiple dips.

This is something that Godin kind of glosses over. You may, indeed, be getting better at your craft over time, and sell some books, but just because you’re getting better doesn’t mean the market is prepared to support you. You can suffer from imploding publishers, bad marketing, bad covers, bad timing, messed up distribution, or any number of external things that can negatively impact your career. If your sales numbers due to these external screw ups are bad enough, it can completely fuck your career.

It can send you right back to the bottom of another dip.

This is where I felt I was when I started reading this book. Like I’d reached some kind of unending slog of a fucking place. On the one hand, yay, my first book did OK! On the other hand, shit, half my sales were ebooks and so when you look on Bookscan (which both other publishers and booksellers do) it looks like I sold half what I actually sold. On Bookscan, it doesn’t look like I have two books that earned out their advances already. It looks like a fucking trainwreck.

And thus: the dip.

I started to wonder why I was still in this writing game, committing myself to a profession with long periods of slog that continually threw me back into the dip. If my definition of success wasn’t money or fame or copies sold, what the fuck was it? Because to stay in this game, I needed to have another metric. I needed something else to drive me forward.

Enter ConFusion, that regional convention I went to. This is the second time I’ve gone. The first time, I felt like an imposter, sort of running around looking for people to talk to like some desperate n00b. I felt wayward in the bar. I did all right on panels, but that writer-stuffed barcon going on felt like something happening in another world. Trying to break into it took more effort than I possessed.

Things happened a little differently this time.

Something has kicked loose in the last two years – maybe because of all the blogging, and how active I am on Twitter – but all the sudden I went from being nobody who didn’t have anyone to talk to to somebody people recognized, and to feeling comfortable around a bunch of writers I’d thought were way out of my “league” (Scalzi has a great post-ConFusion post with baseball metaphors you should check out), most of whom I’d interacted with enough online that they almost felt like old friends.

In truth, I was so relaxed with the small bunch who showed up Thursday night I even had a few drinks with them – usually a no-no for me at cons, which I consider business events (my spouse insists I didn’t say anything I wouldn’t have sober. I just said it MORE LOUDLY). It turned out that folks I knew in passing, or only knew online, were even more awesome in person than they were virtually, which was pretty awesome. Most importantly, I was really comfortable with them, which for somebody introverted and anxiety-ridden like me, was a huge relief. People started coming up to me who certainly didn’t know me two years before. Something had changed in the way folks perceived me. All the sudden, after ten years of slog, some sort of “ah yes, you too are a veteran of this rewarding and yet often so shitty business” thing kicked in, and going to the bar to mingle was suddenly easy instead of anxiety-inducing.

But the most valuable part of this con wasn’t just in feeling like I was part of the community. It was realizing in speaking to folks that it’s fucking hard for everyone. That there are dips in careers. That people you maybe think are selling millions of copies… aren’t. That people you think have quit their day jobs… sure as fuck have not. That sales weren’t always stellar. That reputations built on blog posts are, indeed, only built on blog posts. That everybody fucking hates bad reviews, and fucking reads them anyway.

This is, indeed, the game. There are no guarantees. All you have are the words, and your own persistence.

Going to ConFusion was a really good thing for me. Writers work in isolation, and when you’re yelling at the keyboard, alone, staring at sales numbers, alone, and waiting on responses from potential publishers, alone, it can wear you down. I live in Dayton, Ohio, which doesn’t exactly have a rollickingly community of progressive writers, and my best friend moved away last year, so I’ve been even more isolated than usual recently.

So when I came home from this con, I was reminded that I wasn’t alone, and that not only were there people in my shoes, who had gotten through rough patches like mine, but there were people actively rooting for me, too. A lot of really fantastic people.

Writing fiction, for me, is not like gardening or making terrariums. Writing fiction is something I want to be exceptional at. It’s something I want to continually get better at. It isn’t something I want to quit – no matter how many dips I have to churn through along with my colleagues.

That’s when I realized that my definition of success needed to change. Because if I started chasing big money and sales numbers (which I would still LOVE, naturally, and continue to aspire to), it was highly likely I’d be miserable, at least for a few more years, and then miserable again when, inevitably, I hit another dip. Instead, I needed to have a new definition.

And that definition of success, I realized, was the act of persistence itself.

If I’m still in this game, throwing words at the keyboard and spouting off at cons, a decade, two decades, four decades from now, then fuck it – I’m a success. Because the number of dips I’ll have pushed through and overcome by then will be multitudes.

Winning is bouncing back. Winning is persisting. Your mileage may vary.

The system is made to make as many people fail as possible, and the only part of it you can control is whether or not you get up to fight another day.

That’s all I have.

Like the saying goes, “Fall down seven times. Get up eight.”

That’s the recipe, for me. That’s where the magic happens, for me – that long moment you’re on the mat, sucking air, that seventh time you get hit, when you’re not sure if you can get up.

And then you do.

You get up eight.

Get up.