I was sitting around with some folks at my day job, waiting for another colleague to arrive for a meeting, when someone asked me how my vacation had been. “Oh, the usual,” I said. “I had book deadlines.”

This turned into a discussion about the trials of publishing, book covers, and author control over payments and marketing. After talking about how you only get paid twice a year, at best, and payments are usually late or – in the case of really awful publishers – never show up, one of my colleagues finally asked, “How is that work any better than this work, then? This pays way better.”

And it’s true. I work in marketing and advertising, and it pays much, much better than publishing fiction. In my role, I work on overarching creative concepts and copy, and then I pass things on down the line. My work is seen by tens of thousands of people every day in the form of emails and direct mail pieces, even if those are just brief glances before they bin them.

But marketing pieces are – just like any other big corp piece, from video games to board games to television shows – of necessity, projects created by teams and led by someone who is not the writer. Your words are grist for the mill – they’re just the starting point. Just as I’ve seen stuff I’ve written improve as it goes through the grinder, I’ve also seen incredibly creative work my designer and I came up with utterly eviscerated, stripped of any emotional or creative resonance. That’s the name of the game.

We don’t, ultimately, own our work.

Giving up ownership is what all the money is for.

I hear this from folks in Hollywood and gaming a lot. You’re constrained by budget, by producers who don’t understand your jokes, by networks who want to scrub away the rough edges from your characters. Every corporate endeavor for which you get a livable amount of money, it seems, asks you to care passionately, intensely, about a thing for weeks, months, or years of your life – and then turn it over to some stranger, hoping it’s improved and not mangled (improvement does happen, if you have a really exceptional team; these are magic teams, and if you get one, hold onto them. But for the most part, you must go in expecting to be mangled).

When the work is done, you cash your check and you go home and watch great TV, and read great books, and admire other people’s ad campaigns. And then you have to get yourself all excited to get up again the next day and bleed onto the page for wages, knowing everything you created is most likely destined to be binned, destroyed, dismissed, and eviscerated.

But hey – you aren’t starving. And that’s not something to sniff at.

But hey – you aren’t starving. And that’s not something to sniff at.

The difference between novels and other types of writing is pretty simple, then, when you look at this equation:

Writing novels allows you full control of the words on the page.

Oh, I don’t mean the packaging. Or the marketing of it. Or distribution. You probably will be paid the equivalent of 50 cents an hour of work on the thing, if you’re lucky. And unlike a video game or TV show you’ll be lucky to get a few thousand readers as opposed to a few million.

But the ultimate responsibility for the words on the page is yours. That’s written into pretty much every contract, unless you’re doing some kind of work for hire, writing in an existing universe (and if that language isn’t in your contract, then they’re doing something wrong). Editors and agents and friends and copyeditors can give you suggestions – but these are only suggestions. I suppose you could refuse a copyedit or turn in a blank manuscript and your editor could sever the contract, but for the majority of us – the vast majority – we completely and utterly control the stories we set down on the page from initial concept through publication.

Even if they dump you, you can self-pub the book now at the reasonable cost of your own bloody time and effort.

In a world of madness, where you’re sitting at the bottom of the food chain, feeding your creativity into a machine that gobbles it up and spits out a check, the act of writing a book, the control it affords you over your own words, is a joy in and of itself.

I’ve been a published author for four years now, and yes, it’s very different that just being a writer. What you find is that you start to become the head of a small business. You become that shadowy figure at the top of the food chain you’re feeding your creativity to; you’re the boss, and the people you surround yourself with are, hopefully, folks who can help you create better work, but ultimately you’re in charge of it. You say go. You say stop. You say, “No more.”

Most days, this ultimate control over the words is enough for me. Other days, when the ugly business end rears its monstrous head, it feels like a cold comfort.

One of the bitter lessons I had to learn in this business is that being meek and trusting that everything was going to be fine and other people automatically had a better head for my business than I did wasn’t going to do me any favors. Yes, surround yourself with professionals and take their advice, but just like you’re in charge of the words, you’re in charge of your career, your business, too. Sitting back and hoping good things will happen isn’t doing you any favors.

I have a pretty stellar team of people helping me out now, from my agent to my assistant to the excellent folks at two-out-of-three of my publishers (a good ratio!). But the adjustment of going from someone at the bottom of the food chain, pushing work up and waiting for other people to make decisions about it and giving me direction to realizing I was actually the person managing this whole wacky career thing is still taking some getting used to. That’s hard. And there are a lot of days there isn’t much joy in it.

Schools don’t teach us to be business owners. They teach us to be cogs in machines; the entire system was rigged to turn you into a factory worker. This is a fine mindset for most corporate work, too, as you need to function as a piece of a greater whole. But schools – even college, unless you’re specializing in business – do a poor job of teaching you how to manage, to push, to organize. Instead, you learn to take directions, smile, be pleasant and accommodating.

Becoming a business person often means you must unlearn everything you’ve been taught. It’s deeply uncomfortable.

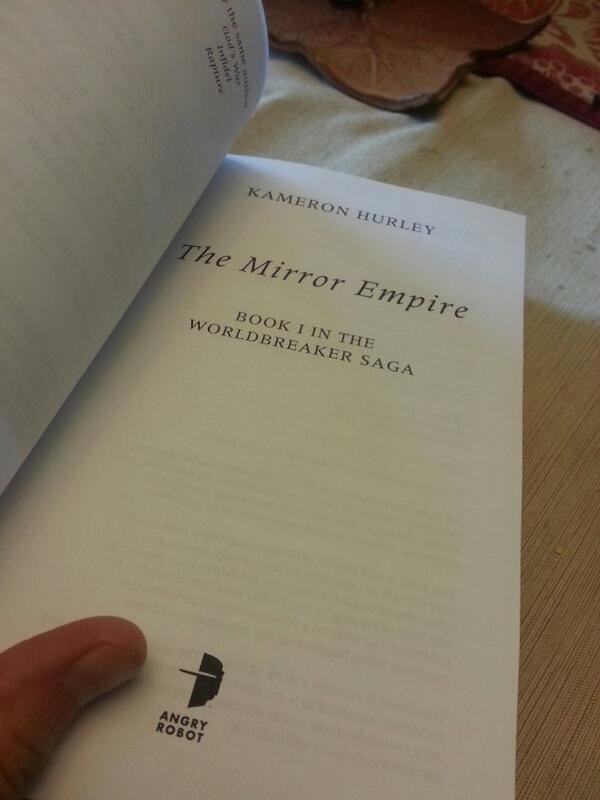

Last night, I received my paper ARC for my new book THE MIRROR EMPIRE. It’s funny, to see your words in printed book form. Something happens when you print and bind words that lends them a heft, a power, that they just don’t have in manuscript form. It goes from looking like Obvious Amateur Hour to Some Great Book From My Favorite Author with a little formatting and paper and glue.

When I opened up that book and started reading, skimming about to my favorite scenes, checking how bad some of the inconsistencies were (just finished a lot of third-act cleanup for final draft), I was reminded, once again, of why I’m doing this despite all the uncomfortable, agonizing bullshit of the business.

When I opened up that book and started reading, skimming about to my favorite scenes, checking how bad some of the inconsistencies were (just finished a lot of third-act cleanup for final draft), I was reminded, once again, of why I’m doing this despite all the uncomfortable, agonizing bullshit of the business.

Because I am writing books for myself. I’m writing these books I wish I had been able to find and read when I was a teenager, books that challenged me to think about the world in new ways, and introduced me to new people and new ways of doing things, all wrapped up in a weird, epic, bloody story.

I’ve lived with these particular characters for a long, long time, waiting until I had (I hoped!) the skill to tell their story properly. Like me, they’ve gotten a bit bitter over time, and they’ll get far darker in books to come. But like me, they’ve endured. They’re still here. And many of them will (probably) make it to the end of the series.

And when I’m done with this series, there will be another series. And another one after that, come what may. There is not a lot of fun on the business side of publishing – and God knows my introduction to the business side of things has been a trial by fire – but seeing that book? Seeing what I made, just as I made it, working so hard with my agent and editor to make into this awesome epic?

That was pretty great. Though I wouldn’t say it was worth all the business bullshit, it does help to mitigate the horror and discomfort of it. I was going to have to learn these things eventually; though I’d have preferred a warm bath to a bucket of cold water. What seeing this book reminds me is that what I’m doing produces the most important tool we have to learn, to tell us who we are – stories. These are the stories that creep up through all of our media, that help us make sense of the world and ourselves.

And I get to make them. With help from the great team of folks I have around me, I get to make them even better than I could on my own, while still owning every word.

That’s my joy. That’s what helps me sleep at night.

That, and a little Tylenol PM.